Adolescence: boys' rage & need

How the cheese and pickle sandwich conveys Jamie's interior world + reflections on the manosphere + why teens do crime + psychoanalytic read of Ep. 3

I watched Adolescence (2025) immediately after a therapist colleague told me she watched the third episode of the series twice. Ep. 3 captures the raw intensity of working as a psychologist with a teen who is starving for validation, even if it means tearing you down to get it. My colleague works at a school and is well acquainted with the the rage and desperate need young people experience when their basic emotional and physical needs are not being met. When they coexist, rage and need create a violent demand for love that expresses itself in what teachers and parents might consider delinquent behavior. If we take teens’ acting out as a cry for help rather than a call for punishment, we can attempt to understand what need is being expressed behind the alarming behavior.

Adolescence is a British mini-series that follows the arrest (Ep. 1), investigation (Ep. 2), assessment (Ep. 3), and family dynamic (Ep. 4) of a teenage boy accused of murdering a young girl from school. Although the show points to the possibility of Jamie, the teen accused of murder, being pushed by the manosphere toward misogyny and femicide, the show depicts a far more complex tapestry of influences that encompass school culture, family relationships, and masculine sexuality. Each episode presents us with another piece of the puzzle to try to piece together how and why an otherwise regular teen would go on to stab a girl multiple times in the chest. Although he leads a normal life, the show punctuates moments of painful deprivation and rejection that seem to suggest that Jamie’s intent grew from the apparently innocuous environment where he was raised. So how is it that a regular, suburban home could raise a killer?

Psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott writes in his paper “The Antisocial Tendency,” that children might act out in order to compensate for the loss or deprivation of good experiences in early life. For instance, a child who steals is not really looking for the stolen object, but is unconsciously trying to regain a good thing that he feels he has rights to. All children experience the feeling of having a right to their mother. That is, they have the hope that when they cry and express their need (even in an annoying way), a mother will be there to provide for them. When the mother is absent, neglectful, or punishing, the child might lose hope that it is possible to have their needs met—thus stealing becomes a clever solution to the problem. By stealing, the child can experience the feeling, unconsciously, of what it’s like to have hope—that is, what it’s like to have the right to have your needs met, even if it means acting as a nuisance to get what you want. This behavior, while annoying or even frightening to adults, Winnicott argues is a sign of hope, a hope that a need can be communicated and met.

Today, it is perhaps common sense that stealing, bullying, and fighting in schools are not behaviors that emerge in a vacuum. They are a response to an environment of deprivation. Adolescence’s main character Jamie commits an unspeakable act, one that is impossible for most to understand. However, the adults in his life, his parents, the detectives, his therapist, all try to put the pieces together, to try to understand why a child who is otherwise a regular kid would commit such an atrocious act. This series unfolds as an attempt to get behind the act, to try to understand what it is that the murder meant to Jamie, what would possibly bring him to do it. The show does not provide us with answers, but it presents us with a series of clues that as an audience we use as a mirror held against our own assumptions about teens and why they do the things they do.

The violent need that you see in Jamie’s assessment with his psychologist in Ep. 3 encapsulates the rage that a lot of teens experience, that goes belittled, pushed aside and ignored. Eventually, that kind of rage transforms into the disturbing behaviors that adults try so hard to quell once its too late. People point their finger at the parents, but the issue is much larger than the nuclear family. It spans the way that schools are structured like prisons, the ways that we treat children and teens as if they are less deserving of respect than adults, and the few rights we grant them to their own bodies (Bell Hooks gives a good account of this in All About Love). I can go on, but will shift to talking about what the series Adolescence gave voice to in regards to the psyche of young men and the uneasy tangle of sex, deprivation, and rage.

Manosphere and Sexual Myths

The discussion surrounding Adolescence has centered the problem of masculinity and the manosphere in influencing youth. The show itself is pretty heavy handed in framing the manosphere as an instigator of its protagonist’s entitled response to his counterpart’s sexual rejection. I won’t go into defining the manosphere, it suffices to say that it is a man-centered culture which seems to use the difference between the sexes as its premise for explaining the issues that befall men. In many ways, it is a philosophy concerned with naturalizing the difference between men and women and contending that these differences are generative of a pervasive sense of loneliness and dissatisfaction for men. They seem to propose that the sexes should be in a symmetric, harmonious relationship to one another—each satisfying the other’s needs. If a woman needs protection, then a man should be a protector. If a man requires sexual stimulation, then a woman should be sexually stimulating.

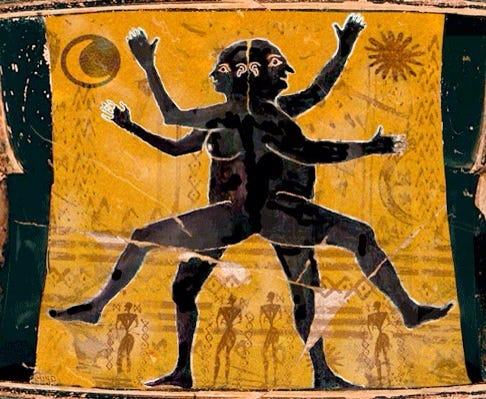

I am opposed to the idea that it is just the manosphere that is proposing these solutions, since the myth that there is such a thing as a perfectly symmetrical and reciprocal sexual relation between the sexes has been at the crux of most cultures. That is to say, the fantasy that men and women are inherently different and that their differences are symmetrical seems to pervade myths, philosophy, and literature across cultures. For instance, in Plato’s Symposium, we get an account of the Myth of Aristophanes and the origins of love, which explains the origin of the sexes. According to this myth, early people were round beings made up of two heads and four of each limb. Eventually, they were struck down the middle by Zeus as a punishment and cursed to live apart until they found their way back to one another again, to form a whole. Thus, love is just finding your way back to your other half, and it explains the wish to merge with the one you love. The reason why this myth endures in a different shape in our culture is because it is so seductive—it suggests that if only we could find our other half, that we would be complete, we would not be lacking. There could be a satisfaction of our desires and emotional needs.

The manosphere is just another community that upholds this myth, that men and women would be happier if they just embodied the complementary characteristics that would make them feel satisfied, complete, and whole. The problem is that real people are not archetypes or perfect amalgams of gendered characteristics. We are complex, frustrating to others, and riddled with desires that have no stable way to get plugged up. The fact of being human means being dissatisfied to some great extent. It means that we strive, we create, and we extend ourselves toward aims to meet our never quenched desires. It is part of what it means to be a person, to be a desiring being.

Adolescence plays with this myth and provides us a more complex depiction of what it means to be really human—that is, what it means to be a desiring being, one with needs and lacks that are not filled, and our ethical responsibility to tend to our own needs without impinging on the rights of others to do so. The unethical (abhorrent) choice that Jamie makes to kill the girl who refused him is a denial of this basic human condition—that frustration, failure, and dissatisfaction are just a part of life. His intolerance of this, of his own lack, fueled by rage, lead to the his tragic choice to kill the one he desired.

Although the show seems to point to Jamie’s involvement with the manosphere, it was only through hearsay. It is not certain what his relationship is to women, but what is evident is what his relationship is to his own masculinity, his rejected needs, and an intolerance of frustration.

The Half Cheese and Pickle Sandwich

Ep. 3 is powerful because it exposes the vulnerability that is still there in spite of all of Jamie’s rage. It seems as if Jamie is fishing for compliments from his psychologist and he gets miffed when she does not respond in a stereotyped way; when she does not tell him that he isn’t ugly, when she withholds encouragement after he disparages himself. We see how he responds to moments of frustration. They are not just small slights, they feel like blows. The wound that she is brushing up against is profound and dark. He lacks the confidence and necessary self-esteem to be able to withstand this kind of frustration. When she denies him consolation, it feels like a direct hit that he must defend himself from. She witnesses his internal process play out in their relationship. Any sign of rejection or slight is perceived as an attack. To defend against this attack, he must hit harder, talk louder, make himself appear threatening. This way, he gets to reject before he gets rejected, he gets to be the one in control of the process of rejection. Otherwise, he would feel like a piece of shit that should just as well be discarded.

We see this rejection dynamic play out in their interaction with the cheese and pickle sandwich. She brings him half a sandwich, something that presumably she may have either eaten later or discarded. He accepts it and takes a little bite, even though, he says, he does not even like pickles. Why accept it and then set it aside, rejecting it only after having held it in his hands? It is as if he is playing out his ambivalence. He wants to receive the gift but he also needs to reject it. He needs to know that she would feed him, but also that he is in all his rights to both receive what she has to give and to reject what she has to offer. In this way, he assumes the position of the one who has a right to a gift but who also has the power to refuse it, to say no, to reject. It is also another way of saying: whatever you have to give is not what I want, it is not what I need. Perhaps he experiences this himself. I mean that he is the one who feels rejected, the one who feels as if he cannot give what others want or need. He shows this to his psychologist throughout his interactions, by identifying with and assuming the role of those who he perceives as powerful because they have the right to demand something of him and to reject what he has to give.

At the peak of the assessment session, we find out where his experience of rejection may have its origin. He associates to a memory of his father averting his gaze when Jamie makes a mistake during a football game. Jamie does not elaborate on the meaning of the averted gaze, but he intuits what it means. He feels it encode in his body as a sign of his father’s feelings of shame. We get a confirmation of this when his father admits to feeling shame when he witnessed his son’s game, and how difficult it was for him to look at his son fail. In other words, he could not claim him as his son by acknowledging him with his gaze. Although Jamie could not put to words what was at stake in this event, it was brought back to memory as something significant. What was significant was precisely that his father could not bring himself to see, could not bring himself to acknowledge him as his own son when he seemed less of a man. He encodes this enigmatic message as an implicit rejection of who he is. It is a rejection that left a bruise that makes all similar slights feel unbearably painful.

To put a Lacanian spin on it, rejection from a father to a son is like an exclusion from the symbolic order, the field in which one can claim an inheritance or a stake in love. The symbolic for Lacan refers to anything to do with culture, language, law, our role and place in social structures in relation to other people in the world. In other words, when the father refuses to claim his son, the son is exiled from his rightful position as inheritor of his father’s place and from what it means to be a man—one who holds a set of symbols and signifiers that indicate his role in the family and in the world.

Once Jamie is cast out from the realm of masculinity, he tries to find his way back in a way that is typical of young men, through the conquest of women. When he is rejected by a woman who he thinks would be easy to pick up, given her abject role in the school as a “flat girl,” he stabs her, as if in a forced penetration. In a way—perhaps—he also aims to kill his father, the One Who Rejects. He tries to kill Rejection itself and to reinstate his own being by annihilating the being of the one who rejects him. It is because of the fragility of his own being in the world, of his status as a son and as a man, that he so easily can negate the being of someone else—one absence in place of his own lack of being. Life means nothing to him, it was not endowed with meaning by a father’s gaze that claims him as his son.

His tantrum with the psychologist at the very end of the assessment session comes at the moment that he recognizes his own desperate need, the lack that constitutes him, and the impossibility of being seen as anything other than a object that deserves rejection. He feels as if the farewell between him and the psychologist is improper, it is not enough that she simply go away and abandon his life, he is still deprived, still lacking what he needs. Her leave represents another cruel rejection; he is so sensitive to rejection, that he cannot bear even a natural ending. Unable to cope, he storms off, subdued by an officer. She too does not claim him as her own, he is again cast away from the promise of acceptance, warmth, and inclusion.

Meanwhile, in the justice system, he is in the process of being assessed and thus defined as a subject of the law. He becomes a person who is defined by the act of murder, a category that he denied right until the very end when he owns up to what he did in Ep 4. He finally embraces the law as a substitute father; the law recognizes him and gives him a place in the world and in the symbolic order: the place of the murderer. Although exiled from the symbolic of the family and culture at large (a kind of symbolic death), he is given a place by the justice system that he is now part of. In the act of transgressing the law (approaching a traumatic real through murder), he is at the same time overtaken by the law. He is between two deaths—he has died in the realm of the family and society at large and is in limbo within the justice system, awaiting a verdict.

When Jamie calls from prison and tells his father that he accepts his guilt, his father is at a loss for words. His mother and sister jump in to fill the silence during their phone call to talk about trivialities, without acknowledging his statement, as if to brush it off and continue in denial. The tragedy of this scene is that Jamie continues not to be recognized by his own family. His most flagrant and undeniable act, the act of a murder, is brushed under the carpet; his attempt to speak into being a truth about his act is ignored and passed over in silence. What he did is unspeakable, the family cannot hold it in speech or understand how it is possible that something like that could happen. An act like murder resists being held down or digested by language. It cannot be processed. This is why there is no satisfying answer that can explain why a teenager would choose to take the life of another. It does not fit anywhere in language. Jamie is recognized by the law, but cannot be recognized or seen by his own kin. He is exiled from the family, from language, and overtaken by the word of the law—an impersonal and punitive Other.

I believe that the reason why it was so hard for him to admit that he had done the crime in the first place is precisely to avoid his father’s rejection, but also to gain in some way his father’s attention. If he were to have admitted early on what he did, could his father really look at him again? He would need to face once again his father’s shame and the aversion of his gaze. By sustaining his innocence, he would get his father’s protection, his father would need to look at him if at least to look after him. To admit his guilt would risk losing his father’s esteem and the possibility of recognition. He props up a false self, a story, to unconsciously gain his father’s love, attention, and protection. There is no doubt why he chose his father, rather than his mother, to be the one alongside him as his designated adult throughout the process. It is his father’s recognition and what it represents in the symbolic (the social sphere, the culture of men) that he needed the most. Rather than revenge or anything related to the manosphere or sexuality, it seems as if his father’s recognition and acceptance is the true and unconscious aim of his crime. This is the tragedy that sustains our sympathy for Jamie—that just like everyone else, there is a protective seed in his body that needed love to grow.

Would love to read your takes on more coming-of-age (if you could argue this as a coming-of-age?) — you have such a profound grasp on it, very insightful and interesting!